Thursday, April 10, 2025

The Frank's Island Lighthouses Come Back to Life!

When I first created this blog, it had been my intention to create paper models of both lighthouses that once stood on Frank's Island. I had actually gotten pretty far along with the tower and lantern of the 1820 lighthouse, but I was not sure how I wanted to handle the base due to its relative size. So I set aside my files and they gathered dust over the years.

A few months ago I got my first 3D printer. After printing out a few free lighthouses, I decided to dust off my Frank's Island Lighthouse drawings and started creating 3D versions of both lighthouses using TinkerCAD. It turns out 3D was not as bad to learn as I thought it would be. I am by no means an expert, but within a few weeks I was able to create decent models of both structures. Here are the Frank's Island Lighthouses in 3D print form!

Friday, June 22, 2012

History Repeats Itself

A modern day repeat of the Frank's Island Lighthouse story...

From the June 14, 2012 Edition of the Franklin Banner-Tribune, Morgan City Daily Review

NEW CAJUN COAST VISITOR CENTER COLLAPSING

by JEAN L. KAESS

The Cajun Coast Welcome and Interpretative Center in Morgan City is in danger of immediate collapse after early reports from the scene indicate its 75-foot pilings may have given way this morning.

The building had sunk approximately 6 feet by press time. Personnel and media on the scene were moved back because of a concern that, if the building did collapse, they might be struck by glass. Officers who approached the building indicated they could still hear it creaking.

Workers notified CCVCB Executive Director Carrie Stansbury around 8:30 a.m. today that there was a problem with the building. Morgan City Police and Fire departments were notified around 9:50 a.m.

“They have no idea what happened,” Stansbury said.

Representatives from every aspect of the building’s planning or building phase were on their way to the interpretative center and expected around press time. The building appears to be sinking in the middle, and photos show water lilies at a level higher than the front door.

Stansbury said the building was scheduled to be completed July 15. The parking lot was a separate project and was due to be completed by the end of the year. She and other local officials had just completed a walk-through of the building Tuesday.

“It is very heart-wrenching to see what is happening to the building right now,” she said.

The building on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard was funded with $1.125 million in state money and more than $2 million in local match. Aegis Construction Inc. of LaPlace is the contractor with Washer Hill Lipscomb Cabanis Architects of Baton Rouge designing the project.

From the June 14, 2012 Edition of the Franklin Banner-Tribune, Morgan City Daily Review

NEW CAJUN COAST VISITOR CENTER COLLAPSING

by JEAN L. KAESS

The Cajun Coast Welcome and Interpretative Center in Morgan City is in danger of immediate collapse after early reports from the scene indicate its 75-foot pilings may have given way this morning.

The building had sunk approximately 6 feet by press time. Personnel and media on the scene were moved back because of a concern that, if the building did collapse, they might be struck by glass. Officers who approached the building indicated they could still hear it creaking.

Workers notified CCVCB Executive Director Carrie Stansbury around 8:30 a.m. today that there was a problem with the building. Morgan City Police and Fire departments were notified around 9:50 a.m.

“They have no idea what happened,” Stansbury said.

Representatives from every aspect of the building’s planning or building phase were on their way to the interpretative center and expected around press time. The building appears to be sinking in the middle, and photos show water lilies at a level higher than the front door.

Stansbury said the building was scheduled to be completed July 15. The parking lot was a separate project and was due to be completed by the end of the year. She and other local officials had just completed a walk-through of the building Tuesday.

“It is very heart-wrenching to see what is happening to the building right now,” she said.

The building on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard was funded with $1.125 million in state money and more than $2 million in local match. Aegis Construction Inc. of LaPlace is the contractor with Washer Hill Lipscomb Cabanis Architects of Baton Rouge designing the project.

Friday, December 17, 2010

A Piece of FILH History Hits the Auction Block

I just found out that a piece of Frank's Island Lighthouse history was up for auction last month. A leather bound ledger book containing the signature of Benjamin Beal, one of Winslow Lewis' sub-contractors, was put up for auction by a New Orleans-based auction house. The contents of this ledger contained lists of workers, organized by month, from April 1818 to April 1823, indicating the days worked per month for each worker. As a ledger, this book does not seem to contain any significantly historal information, such as a description of the first lighthouse's collapse or a drawing of the second lighthouse. There are, however, some interesting nuggets of information listed in the auction description that give a glimpse into life on Frank's Island while the lighthouses were being constructed.

According to the auction listing, the opening bid for the ledger was $400 and the auction house informs me that it sold for $800. From a research perspective, I am not certain this book contains any information that would help clarify the cloudy mystery surrounding the Frank's Island Lighthouses. I am amazed that any kind of written record that was present on Frank's Island during the construction of the lighthouses exists today! Deep down, the finding of this ledger's existence gives me hope that a personal journal from someone who spent time on Frank's Island, or letters between the sub-contractors and Winslow Lewis, will turn up during my lifetime...

Here is the description of the ledger from the auction listing:

Frank Island Lighthouse*, An Account of the Time Building the Light House on Frank Island, New Orleans, ledger with watermarked, laid paper, three quarter leather boards, manuscript entries, one month per page, covering the period from March 1, 1818 through April 17, 1823, the front paste down signed "Benjamin Beal, Hingham, 1818", each page noting the days worked by each worker, with various notes scattered throughout including; "cutting wood up the river", "stole a boat and absconded".

Here is a link to the listing containing some pictures of the ledger book...

http://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/8169137

*Notice it is referred to as "Frank Island" in Beal's ledger.

According to the auction listing, the opening bid for the ledger was $400 and the auction house informs me that it sold for $800. From a research perspective, I am not certain this book contains any information that would help clarify the cloudy mystery surrounding the Frank's Island Lighthouses. I am amazed that any kind of written record that was present on Frank's Island during the construction of the lighthouses exists today! Deep down, the finding of this ledger's existence gives me hope that a personal journal from someone who spent time on Frank's Island, or letters between the sub-contractors and Winslow Lewis, will turn up during my lifetime...

Here is the description of the ledger from the auction listing:

Frank Island Lighthouse*, An Account of the Time Building the Light House on Frank Island, New Orleans, ledger with watermarked, laid paper, three quarter leather boards, manuscript entries, one month per page, covering the period from March 1, 1818 through April 17, 1823, the front paste down signed "Benjamin Beal, Hingham, 1818", each page noting the days worked by each worker, with various notes scattered throughout including; "cutting wood up the river", "stole a boat and absconded".

Here is a link to the listing containing some pictures of the ledger book...

http://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/8169137

*Notice it is referred to as "Frank Island" in Beal's ledger.

Thursday, April 1, 2010

The Case of the Missing Lighthouse Marker

When I first began researching the Frank's Island Lighthouse, pictures and drawings were difficult to come by... And then one day I discovered the Historic American Buildings Survey online database. As I perused the pictures Samuel Wilson, Jr. took in November of 1934, I became captivated by the close-up of the marble marker embedded in the brickwork just above the doorway. Instinctively I knew this remarkable component did not belong to the otherwise homely structure. It suddenly dawned on me that this marble marker was perhaps the only remaining piece of Latrobe's Lighthouse. By closely studying the aerial photograph of the Frank's Island Lighthouse taken by Bob and Sandra Shanklin in 1995, I realized that the marker was now missing! At that moment, I made it my quest to locate this historic artifact. Here is the story of my endeavor to re-discover this piece of history in a Post-Katrina New Orleans as written in February 2007...

Most journeys begin with a destination in mind. On this journey, the destination was unclear. In this case, there were two lighthouses – one that was short-lived and one that had recently collapsed. Their location was, at one time, known as Frank’s Island, Louisiana – located at the Northeast Pass of the Mississippi River. Today, nothing remains of Frank’s Island. The island has been consumed by erosion and is now totally engulfed by a body of water called Blind Bay.

Many people are aware of the history behind the Frank’s Island Lighthouses. President Thomas Jefferson ordered Congress to establish a navigational beacon to mark the entrance to the Mississippi River. The lighthouse that Jefferson had in mind was no ordinary lighthouse. He wanted a monument to show the world that the Louisiana Territory no longer belonged to the French. To design such a grand lighthouse, Congress selected renowned architect and engineer, Benjamin Henry Latrobe – the designer of the United States Capitol. Eventually, Frank’s Island was chosen as the location; but a little spat between the United States and England, called the War of 1812, got into the way. Finally, in 1818 Congress authorized construction of the lighthouse and work began. The not-yet-famous lighthouse builder, Winslow Lewis, was awarded the contract to construct the lighthouse. There are questions as to why the “Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River” began to settle severely and develop cracks; but the original lighthouse had to be torn down and a new one was erected in its place. The second lighthouse, designed and built by none other than Winslow Lewis, was completed in 1823.

At this point, the history of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse becomes vague. There are no known pictures of the structure with a complete lantern room. As other entrances to the Mississippi River became more popular, the Northeast Pass and the Frank’s Island Lighthouse were abandoned in 1856. The journey does not continue again until 1934 when architect and descendant of Latrobe, Samuel Wilson, Jr., inspected the ruins of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse for the Historic American Buildings Survey. As a result of this survey, he composed a written report, took several black and white photographs, and drew a scale drawing of the tower. One of the most intriguing elements of Wilson’s inspection is a photograph of a marble builders marker set into the brickwork of the lighthouse, just above the doorway. The marker reads, “Erected in 1823, Contracted for by Winslow Lewis of Boston, Executed by Benjamin Beal and Duncan McB. Thaxter.” All three of these gentlemen are credited in the construction of the first lighthouse at Frank’s Island. What really makes this marker stand out is an observation that Samuel Wilson makes in his report. He noted that the date on the marker did not appear to be the original date. Apparently the “3” had been recarved over a “0” making the date 1820 – the year that Latrobe’s lighthouse had been erected. Is it possible that this builders marker from the second lighthouse served as a builders marker for the original lighthouse?

The next step of the journey begins and ends with an aerial photograph taken of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse in 1995. By 2002, the ruins of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse collapsed into Blind Bay – eventually meeting the fate of its predecessor. The lighthouse is now all but forgotten. The construction of the original lighthouse is remembered as a sort of folly; there are no outstanding photographs of either lighthouse; and the only significant remnant that could possibly be tied to both structures collapsed into Blind Bay and is probably covered by several feet of dark mud. But is that the end of the story? Is Thomas Jefferson’s vision of a grand lighthouse at the mouth of the Mighty Mississippi to end with the unheard collapse of a second lighthouse? Or will this marble marker one day be uncovered by a storm and be discovered by some future historian who will carry on its legend and its legacy?

It has been said that a photograph is worth a thousand words. In this case, a closer inspection of a photograph of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse taken in 1995 by Bob and Sandra Shanklin yielded a whole new beginning to this journey. It just so happens that the 1995 photograph was taken of the east face of the tower. The picture taken in 1934 by Samuel Wilson, Jr. is also of the east face. The difference between the two photographs is the marker from the earlier picture is missing in the more recent picture! Where could it have gone? Could it be in a museum? Was the marble slab removed by vandals and sold to a private collector? At this point in the journey, the destination became unclear.

Fortunately, the journey continued not far from where the last phase ended. Bob Shankin vaguely remembered that a marker from the Frank’s Island Lighthouse was on display at one of the old Civil War forts around New Orleans. As history would have it, New Orleans was heavily fortified at the time of the Civil War by no fewer than eight active fortifications. However, only two of these old forts are open to the public – Fort Pike in New Orleans and Fort Jackson in Buras, Louisiana.

Now there is a fork in the road. With these two forts being about 55 miles apart it should not be difficult to get into a car and visit both forts in one day. Up until August 29, 2005, this trip would have been no problem. However, both forts were overwhelmed by the forces of Hurricane Katrina. Fort Pike suffered a direct blow - opening three-foot wide cracks in its walls. Fort Jackson was flooded by Hurricane Katrina and then re-flooded almost one month later by Hurricane Rita. So, no matter which direction is taken, the journey is cut short.

It has been a year-and-a-half since Hurricane Katrina. The city of New Orleans is slowly coming back to only a fraction of what it once was. The people in New Orleans and its outer-lying parishes are a proud people doing the best they can to restore their homes and their lives. What they knew to be beautiful, what they knew to be mundane, most of everything they knew has been destroyed. What has been reclaimed of their memories has been accomplished through hard work and patience. It would seem that a long forgotten remnant of history would have no place in their current strifes. But that is not the case…

A few quick phone calls to the Louisiana Office of State Parks made it apparent that Fort Pike had not been forgotten. Work was done to clean the layer of muck and debris that was deposited throughout the fort’s interior. Any artifacts belonging to the Fort Pike Museum were gathered, cleaned, and preserved for future display. Engineers have been called in to assess the damage caused to the fort’s structure by Hurricane Katrina. It will be some time before this fort will be open to the public – if it is ever opened again. One item that was not listed in the fort’s inventory of artifacts – a marble marker removed from the Frank’s Island Lighthouse. So, the journey continues…

Plaquemines Parish was so heavily hit by Hurricane Katrina that only the first few miles of Highway 23 were accessible for weeks. As an outer-lying parish, Plaquemines Parish is having a much more difficult time getting back on its feet. The same is true for Fort Jackson. Whereas Fort Pike is managed by the Louisiana Office of State Parks and is funded by the State, Fort Jackson is managed by the local municipality. This makes funding for restoration efforts more difficult. Despite these difficulties, the people in Plaquemines Parish were very helpful and courteous. The Parish Historian, Rod Lincoln, was very knowledgeable about Frank’s Island Lighthouse and all of the other lighthouses that marked the Passes. Without hesitation, Mr. Lincoln was able to confirm that the marble marker from the Frank’s Island Lighthouse is now on display at Fort Jackson. However, like its sister fort, Fort Jackson is also closed to the public for an indefinite period of time.

At this point, the mystery is solved and the story ends. But, as in every good story about a journey, there is a hero. The hero in this story is a Mississippi River boat pilot named Captain Mark Delesdernier, Jr. As a child, Captain Delesdernier had the opportunity to frequent the Frank’s Island Lighthouse – its lantern-less tower now standing in waist-deep water. He was captivated by the marble cornerstone of the lighthouse and read its inscription often. Over time, the mortar around the marker gave way, and the marble slab became loosened from its one-hundred-fifty-year-old resting place. At some point, the bottom right corner of the marker was damaged and a small section broke off. By the late 1960’s, the cornerstone was released from its encasement and it fell into the water. On a warm sunny day, Captain Delesdernier dove into the water and began feeling around for the marker. With luck, he found its resting place at the bottom of the bay! He used a small flatboat and a rigging of pipes and rope, positioned through the doorway of the old lighthouse ruins, to raise the eight-hundred-pound slab of marble from the water. As soon as he got the marker into the boat, the weight of the marble slab caused the boat to sink – requiring Captain Delesdernier to get a bigger boat. Eventually, he donated the cornerstone to the people of Plaquemines Parish. A new resting place was hewn out of the brick interior of Fort Jackson, and the marble marker was re-encased into its new home – once again on display. A metal plaque was then placed over the Frank’s Island Marker by the Plaquemines Parish Commission Council to illustrate the marker’s history and to honor its dedication. Whether or not Captain Delesdernier truly knew the history behind the lighthouse and the marker, he is a hero for saving this piece of history before it was lost to the muddy waters of Blind Bay and forgotten.

At the end of every journey, one should reflect and take the time to look at the pictures. In this journey, there are a few things to ponder. The journey began with President Thomas Jefferson when he ordered that a monumental lighthouse was to be erected. It then went to Benjamin Henry Latrobe and a grand lighthouse was designed. Next it fell into the hands of Winslow Lewis. An exquisite lighthouse was built, only to be torn down almost immediately due to a failure of its foundation. At this point, did Winslow Lewis recover the builders marker from the first lighthouse and save it for a future replacement? One only has to look at Samuel Wilson’s photographs of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse to realize the answer. There is nothing elaborate about the second lighthouse built in 1823 with the exception of the marble marker. Lewis made only one commitment to Congress in regards to the second lighthouse – that he would guarantee its foundation. Unlike his predecessor, Benjamin Latrobe, Lewis was not hired to design a monument. He just had to build the 1823 lighthouse so that it would not collapse. To have such a large piece of marble cut and shipped from the East Coast would have been an unnecessary expense for Lewis. Therefore, it is probable that this marker is the only remaining identifiable object to have served as part of the structure for the Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River as ordered by President Thomas Jefferson. Incidentally, Fort Jackson was erected around the same time as the lighthouses at Frank’s Island were being constructed. It is somewhat ironic that a fortification built to guard the first Capitol of the Louisiana Territory now stands to shelter a piece of a lighthouse that once guided sailing vessels safely to the mighty river that runs through it – two remnants of Thomas Jefferson’s legacy, living in the past, huddling together as though waiting out another storm.

Author's Note - At the time I had written this article, I thought I was really onto something, having discovered a historical and structural link between the two lighthouses constructed on Frank's Island. My later research findings show that authors David L. Cipra and Janice P. Buras had also written about the marble marker and its commonality to both lighthouses. In her book, "Way Down Yonder in Plaquemines Parish", Ms. Buras tells the story of the marker's recovery and its current placement in Fort Jackson. Had I discovered her book before I began my quest to find the marker, it would have surely saved me some time and effort! It is highly likely that Samuel Wilson, Jr. also made the same connection of the marker having been used in the construction of both lighthouses, but I have not been able to verify this as yet. The pictures below illustrate the marker's journey from Frank's Island to Fort Jackson...

Most journeys begin with a destination in mind. On this journey, the destination was unclear. In this case, there were two lighthouses – one that was short-lived and one that had recently collapsed. Their location was, at one time, known as Frank’s Island, Louisiana – located at the Northeast Pass of the Mississippi River. Today, nothing remains of Frank’s Island. The island has been consumed by erosion and is now totally engulfed by a body of water called Blind Bay.

Many people are aware of the history behind the Frank’s Island Lighthouses. President Thomas Jefferson ordered Congress to establish a navigational beacon to mark the entrance to the Mississippi River. The lighthouse that Jefferson had in mind was no ordinary lighthouse. He wanted a monument to show the world that the Louisiana Territory no longer belonged to the French. To design such a grand lighthouse, Congress selected renowned architect and engineer, Benjamin Henry Latrobe – the designer of the United States Capitol. Eventually, Frank’s Island was chosen as the location; but a little spat between the United States and England, called the War of 1812, got into the way. Finally, in 1818 Congress authorized construction of the lighthouse and work began. The not-yet-famous lighthouse builder, Winslow Lewis, was awarded the contract to construct the lighthouse. There are questions as to why the “Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River” began to settle severely and develop cracks; but the original lighthouse had to be torn down and a new one was erected in its place. The second lighthouse, designed and built by none other than Winslow Lewis, was completed in 1823.

At this point, the history of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse becomes vague. There are no known pictures of the structure with a complete lantern room. As other entrances to the Mississippi River became more popular, the Northeast Pass and the Frank’s Island Lighthouse were abandoned in 1856. The journey does not continue again until 1934 when architect and descendant of Latrobe, Samuel Wilson, Jr., inspected the ruins of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse for the Historic American Buildings Survey. As a result of this survey, he composed a written report, took several black and white photographs, and drew a scale drawing of the tower. One of the most intriguing elements of Wilson’s inspection is a photograph of a marble builders marker set into the brickwork of the lighthouse, just above the doorway. The marker reads, “Erected in 1823, Contracted for by Winslow Lewis of Boston, Executed by Benjamin Beal and Duncan McB. Thaxter.” All three of these gentlemen are credited in the construction of the first lighthouse at Frank’s Island. What really makes this marker stand out is an observation that Samuel Wilson makes in his report. He noted that the date on the marker did not appear to be the original date. Apparently the “3” had been recarved over a “0” making the date 1820 – the year that Latrobe’s lighthouse had been erected. Is it possible that this builders marker from the second lighthouse served as a builders marker for the original lighthouse?

The next step of the journey begins and ends with an aerial photograph taken of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse in 1995. By 2002, the ruins of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse collapsed into Blind Bay – eventually meeting the fate of its predecessor. The lighthouse is now all but forgotten. The construction of the original lighthouse is remembered as a sort of folly; there are no outstanding photographs of either lighthouse; and the only significant remnant that could possibly be tied to both structures collapsed into Blind Bay and is probably covered by several feet of dark mud. But is that the end of the story? Is Thomas Jefferson’s vision of a grand lighthouse at the mouth of the Mighty Mississippi to end with the unheard collapse of a second lighthouse? Or will this marble marker one day be uncovered by a storm and be discovered by some future historian who will carry on its legend and its legacy?

It has been said that a photograph is worth a thousand words. In this case, a closer inspection of a photograph of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse taken in 1995 by Bob and Sandra Shanklin yielded a whole new beginning to this journey. It just so happens that the 1995 photograph was taken of the east face of the tower. The picture taken in 1934 by Samuel Wilson, Jr. is also of the east face. The difference between the two photographs is the marker from the earlier picture is missing in the more recent picture! Where could it have gone? Could it be in a museum? Was the marble slab removed by vandals and sold to a private collector? At this point in the journey, the destination became unclear.

Fortunately, the journey continued not far from where the last phase ended. Bob Shankin vaguely remembered that a marker from the Frank’s Island Lighthouse was on display at one of the old Civil War forts around New Orleans. As history would have it, New Orleans was heavily fortified at the time of the Civil War by no fewer than eight active fortifications. However, only two of these old forts are open to the public – Fort Pike in New Orleans and Fort Jackson in Buras, Louisiana.

Now there is a fork in the road. With these two forts being about 55 miles apart it should not be difficult to get into a car and visit both forts in one day. Up until August 29, 2005, this trip would have been no problem. However, both forts were overwhelmed by the forces of Hurricane Katrina. Fort Pike suffered a direct blow - opening three-foot wide cracks in its walls. Fort Jackson was flooded by Hurricane Katrina and then re-flooded almost one month later by Hurricane Rita. So, no matter which direction is taken, the journey is cut short.

It has been a year-and-a-half since Hurricane Katrina. The city of New Orleans is slowly coming back to only a fraction of what it once was. The people in New Orleans and its outer-lying parishes are a proud people doing the best they can to restore their homes and their lives. What they knew to be beautiful, what they knew to be mundane, most of everything they knew has been destroyed. What has been reclaimed of their memories has been accomplished through hard work and patience. It would seem that a long forgotten remnant of history would have no place in their current strifes. But that is not the case…

A few quick phone calls to the Louisiana Office of State Parks made it apparent that Fort Pike had not been forgotten. Work was done to clean the layer of muck and debris that was deposited throughout the fort’s interior. Any artifacts belonging to the Fort Pike Museum were gathered, cleaned, and preserved for future display. Engineers have been called in to assess the damage caused to the fort’s structure by Hurricane Katrina. It will be some time before this fort will be open to the public – if it is ever opened again. One item that was not listed in the fort’s inventory of artifacts – a marble marker removed from the Frank’s Island Lighthouse. So, the journey continues…

Plaquemines Parish was so heavily hit by Hurricane Katrina that only the first few miles of Highway 23 were accessible for weeks. As an outer-lying parish, Plaquemines Parish is having a much more difficult time getting back on its feet. The same is true for Fort Jackson. Whereas Fort Pike is managed by the Louisiana Office of State Parks and is funded by the State, Fort Jackson is managed by the local municipality. This makes funding for restoration efforts more difficult. Despite these difficulties, the people in Plaquemines Parish were very helpful and courteous. The Parish Historian, Rod Lincoln, was very knowledgeable about Frank’s Island Lighthouse and all of the other lighthouses that marked the Passes. Without hesitation, Mr. Lincoln was able to confirm that the marble marker from the Frank’s Island Lighthouse is now on display at Fort Jackson. However, like its sister fort, Fort Jackson is also closed to the public for an indefinite period of time.

At this point, the mystery is solved and the story ends. But, as in every good story about a journey, there is a hero. The hero in this story is a Mississippi River boat pilot named Captain Mark Delesdernier, Jr. As a child, Captain Delesdernier had the opportunity to frequent the Frank’s Island Lighthouse – its lantern-less tower now standing in waist-deep water. He was captivated by the marble cornerstone of the lighthouse and read its inscription often. Over time, the mortar around the marker gave way, and the marble slab became loosened from its one-hundred-fifty-year-old resting place. At some point, the bottom right corner of the marker was damaged and a small section broke off. By the late 1960’s, the cornerstone was released from its encasement and it fell into the water. On a warm sunny day, Captain Delesdernier dove into the water and began feeling around for the marker. With luck, he found its resting place at the bottom of the bay! He used a small flatboat and a rigging of pipes and rope, positioned through the doorway of the old lighthouse ruins, to raise the eight-hundred-pound slab of marble from the water. As soon as he got the marker into the boat, the weight of the marble slab caused the boat to sink – requiring Captain Delesdernier to get a bigger boat. Eventually, he donated the cornerstone to the people of Plaquemines Parish. A new resting place was hewn out of the brick interior of Fort Jackson, and the marble marker was re-encased into its new home – once again on display. A metal plaque was then placed over the Frank’s Island Marker by the Plaquemines Parish Commission Council to illustrate the marker’s history and to honor its dedication. Whether or not Captain Delesdernier truly knew the history behind the lighthouse and the marker, he is a hero for saving this piece of history before it was lost to the muddy waters of Blind Bay and forgotten.

At the end of every journey, one should reflect and take the time to look at the pictures. In this journey, there are a few things to ponder. The journey began with President Thomas Jefferson when he ordered that a monumental lighthouse was to be erected. It then went to Benjamin Henry Latrobe and a grand lighthouse was designed. Next it fell into the hands of Winslow Lewis. An exquisite lighthouse was built, only to be torn down almost immediately due to a failure of its foundation. At this point, did Winslow Lewis recover the builders marker from the first lighthouse and save it for a future replacement? One only has to look at Samuel Wilson’s photographs of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse to realize the answer. There is nothing elaborate about the second lighthouse built in 1823 with the exception of the marble marker. Lewis made only one commitment to Congress in regards to the second lighthouse – that he would guarantee its foundation. Unlike his predecessor, Benjamin Latrobe, Lewis was not hired to design a monument. He just had to build the 1823 lighthouse so that it would not collapse. To have such a large piece of marble cut and shipped from the East Coast would have been an unnecessary expense for Lewis. Therefore, it is probable that this marker is the only remaining identifiable object to have served as part of the structure for the Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River as ordered by President Thomas Jefferson. Incidentally, Fort Jackson was erected around the same time as the lighthouses at Frank’s Island were being constructed. It is somewhat ironic that a fortification built to guard the first Capitol of the Louisiana Territory now stands to shelter a piece of a lighthouse that once guided sailing vessels safely to the mighty river that runs through it – two remnants of Thomas Jefferson’s legacy, living in the past, huddling together as though waiting out another storm.

Author's Note - At the time I had written this article, I thought I was really onto something, having discovered a historical and structural link between the two lighthouses constructed on Frank's Island. My later research findings show that authors David L. Cipra and Janice P. Buras had also written about the marble marker and its commonality to both lighthouses. In her book, "Way Down Yonder in Plaquemines Parish", Ms. Buras tells the story of the marker's recovery and its current placement in Fort Jackson. Had I discovered her book before I began my quest to find the marker, it would have surely saved me some time and effort! It is highly likely that Samuel Wilson, Jr. also made the same connection of the marker having been used in the construction of both lighthouses, but I have not been able to verify this as yet. The pictures below illustrate the marker's journey from Frank's Island to Fort Jackson...

Close-up of Lighthouse Doorway from Latrobe's Drawing Showing Marker

Close-up of Lighthouse Doorway from Latrobe's Drawing Showing Marker

.jpg) Picture of the Marble Marker - Historic American Buildings Survey

Picture of the Marble Marker - Historic American Buildings Survey

Picture of Marble Marker now at Fort Jackson - Buras, Louisiana

Picture of Marble Marker now at Fort Jackson - Buras, Louisiana

Close-up of Plaque Above Marker

Close-up of Plaque Above Marker

Last Two Pictures are Courtesy of Rod Lincoln, Plaquemines Parish Historian

Friday, August 21, 2009

"The Weight" - Winslow Lewis’ Validation of Benjamin Latrobe’s Design for a Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River

There is an underlying tone contained within this blog that demonstrates a lack of faith in the design, engineering, and construction abilities of Winslow Lewis. Even researchers who feel Lewis was “the right man at the right time”, such as Richard W. Updike, make these assertions with a certain lack of conviction. No matter what opinion one may have of Winslow Lewis, he did accomplish what was thought to be impossible… He was able construct a stable masonry lighthouse structure on the soft soil of the Mississippi River Delta. What makes this achievement more impressive is the fact that he went before Congress and guaranteed that he could do so despite Latrobe’s apparent failure to achieve the same. As a further credit to Lewis in these endeavors, he was able to repeat his success; but not without some failures in between.

The 1823 Frank’s Island Lighthouse stood for 179 years before it collapsed. It had sunken about 3 to 4 feet at the time it was surveyed by Samuel Wilson, Jr.; but it served its purpose without failure or disappointment until it was discontinued in 1856. Between 1831 and 1840, Lewis constructed several other lighthouses on the Mississippi River Delta. These challenges were met with very limited success. Towers at the South and Southwest Passes were undermined by water currents and collapsed. The only other success Lewis had with constructing a masonry lighthouse on the Mississippi Delta is the 1840 Southwest Pass Lighthouse. Even though the tower of this lighthouse was 10 feet shorter than that of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse, the second Southwest Pass Lighthouse began to list shortly after construction. Despite this flaw and a rather disappointing service record, the structure is still standing after 169 years.

Due to the mixed successes and failures of Lewis’ masonry towers on the Mississippi Delta, one could reasonably question whether his success with the Frank’s Island Lighthouse was a fluke. If Winslow Lewis truly knew how to erect a masonry tower on alluvium soil, why could he not faithfully duplicate his earlier success? The Frank’s Island Lighthouse tower was 75 feet tall – at least 10 feet taller than any of the other masonry towers he built along the Mississippi. Therefore, it was the heaviest of the lot. Even though weight was his major concern and criticism with Latrobe’s Lighthouse, Lewis achieved his greatest success in the area with the largest and heaviest structure he built. What kind of foundation did Lewis choose to erect the 1823 Lighthouse? Did he possibly borrow from Latrobe's foundation design, but chose to get it right the second time around? One may never be able to answer these questions without excavating the site now six or so feet under water. The only reference I could find relating to a foundation specification for one of these masonry lighthouses is taken from David Cipra's "Lighthouses & Lightships of the Northern Gulf of Mexico" regarding the original Southwest Pass Lighthouse...

"In 1842, a Congressman charged that the first tower was shoddily built 'on a foundation of old flatboat planks at a cost of $10,011.74' The construction contract had called for a foundation of pilings driven 40 feet, or as far as a 1,400-pound weight falling 26 feet could pound them."

I can only assume that Congress would have specified a foundation based on that of the proven 1823 tower’s design. It would also seem that Lewis’ limited success with these structures may have been hindered by his propensity to take shortcuts as he did with Latrobe’s Lighthouse. Regardless of his haphazard efforts, Lewis did get it right the first time, and this is where Lewis, himself, has inadvertently validated Latrobe’s lighthouse design…

What are you supposed to do if you are walking on the surface of a frozen pond and the ice begins to crack under your feet? You are supposed to lie down and spread your weight across as much of the ice’s surface as you can. By lying down on the ice, do you weigh less? No, you weigh the same; but by lying down, your weight is no longer concentrated within the area of your feet. Instead, it is spread across the entire area of your body. By spreading your weight, you are exerting less pressure across the overall surface of the ice. This is the same thought process that Benjamin Latrobe used in designing his lighthouse. On page 246 of the article, “Benjamin Latrobe’s Designs for a Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River”, Dr. Michael W. Fazio offers an extensive analysis of the efforts Latrobe made to lighten the structure and to spread its weight over as large an area as possible. According to the article (Footnote 68), “The area of a 108-ft. diameter circle is 9156 sq. ft. A reasonable pile-mat bearing capacity for the blue clay soil would be about 1500 pounds per square foot; therefore 9156 sq. ft. times 1500 lbs. per sq. ft. equals 13,734,360 pounds, the allowable load that the pile-mat should have supported… If an average weight for the brick and stone masonry is assumed to be 150 pounds per cubic foot, then the total weight of the lighthouse was 36,000 cu. ft. times 150 lbs. per cu. ft. equals 5,400,000 pounds – well below the allowable load. Ruddock, in his report, said that the tower had a masonry volume of 24,667 cu. ft. and weighed 3,154,625 pounds.” Using Dr. Fazio’s analysis, one can divide the weight of Latrobe’s Lighthouse (3,154,625 pounds) into the load bearing capacity of the soil its weight was spread across (13,734,360 pounds) and conclude that the structure came in at only 23% of the soil’s load bearing capacity. Based on this analysis alone, it should be evident that weight was not cause of the structure’s failure.

Now, if one applies the same analysis to Lewis’ lighthouse, a different result comes to light. A truncated cone with a lower diameter of 28 feet, an upper diameter of 22 feet, and a height of 75 feet, has a volume of 37,000 cubic feet. Wilson's survey drawing indicates that Lewis' tower had two 18-inch thick brick walls, one inside the other with a 1-foot space in between. My conservative approximation would suggest that the tower was 25% solid, yielding a masonry volume of 9,250 cubic feet. The masonry weight of the tower would be approximately 1,387,500 pounds. Although the base of the lighthouse was 28 feet in diameter, let's assume that it sat on a foundation platform that measured 30 feet in diameter – less than 1/3rd. the diameter of Latrobe’s structure. This would yield a base surface area of 707 square feet, resulting load bearing capacity of 1,060,500 pounds. If my calculations are even remotely correct, then Lewis' tower weighed 327,000 pounds or 31% over the load capacity of the strata it sat upon! Even though Lewis’s lighthouse weighed about 1/3rd. less than Latrobe’s lighthouse, its weight was spread over a much smaller surface area. Perhaps this is why the structure had sunken 3 to 4 feet over the course of 111 years. However, if weight was the key flaw in Latrobe’s design, then Lewis’ lighthouse should have met a similar fate in as short a time. Instead, his tower, which exceeded the load bearing capacity of the soil it sat upon by 31%, continued to stand for 179 years. Winslow Lewis, through the success of his 1823 lighthouse, proved that it was not the weight of Latrobe's lighthouse which caused its untimely failure!

The 1823 Frank’s Island Lighthouse stood for 179 years before it collapsed. It had sunken about 3 to 4 feet at the time it was surveyed by Samuel Wilson, Jr.; but it served its purpose without failure or disappointment until it was discontinued in 1856. Between 1831 and 1840, Lewis constructed several other lighthouses on the Mississippi River Delta. These challenges were met with very limited success. Towers at the South and Southwest Passes were undermined by water currents and collapsed. The only other success Lewis had with constructing a masonry lighthouse on the Mississippi Delta is the 1840 Southwest Pass Lighthouse. Even though the tower of this lighthouse was 10 feet shorter than that of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse, the second Southwest Pass Lighthouse began to list shortly after construction. Despite this flaw and a rather disappointing service record, the structure is still standing after 169 years.

Due to the mixed successes and failures of Lewis’ masonry towers on the Mississippi Delta, one could reasonably question whether his success with the Frank’s Island Lighthouse was a fluke. If Winslow Lewis truly knew how to erect a masonry tower on alluvium soil, why could he not faithfully duplicate his earlier success? The Frank’s Island Lighthouse tower was 75 feet tall – at least 10 feet taller than any of the other masonry towers he built along the Mississippi. Therefore, it was the heaviest of the lot. Even though weight was his major concern and criticism with Latrobe’s Lighthouse, Lewis achieved his greatest success in the area with the largest and heaviest structure he built. What kind of foundation did Lewis choose to erect the 1823 Lighthouse? Did he possibly borrow from Latrobe's foundation design, but chose to get it right the second time around? One may never be able to answer these questions without excavating the site now six or so feet under water. The only reference I could find relating to a foundation specification for one of these masonry lighthouses is taken from David Cipra's "Lighthouses & Lightships of the Northern Gulf of Mexico" regarding the original Southwest Pass Lighthouse...

"In 1842, a Congressman charged that the first tower was shoddily built 'on a foundation of old flatboat planks at a cost of $10,011.74' The construction contract had called for a foundation of pilings driven 40 feet, or as far as a 1,400-pound weight falling 26 feet could pound them."

I can only assume that Congress would have specified a foundation based on that of the proven 1823 tower’s design. It would also seem that Lewis’ limited success with these structures may have been hindered by his propensity to take shortcuts as he did with Latrobe’s Lighthouse. Regardless of his haphazard efforts, Lewis did get it right the first time, and this is where Lewis, himself, has inadvertently validated Latrobe’s lighthouse design…

What are you supposed to do if you are walking on the surface of a frozen pond and the ice begins to crack under your feet? You are supposed to lie down and spread your weight across as much of the ice’s surface as you can. By lying down on the ice, do you weigh less? No, you weigh the same; but by lying down, your weight is no longer concentrated within the area of your feet. Instead, it is spread across the entire area of your body. By spreading your weight, you are exerting less pressure across the overall surface of the ice. This is the same thought process that Benjamin Latrobe used in designing his lighthouse. On page 246 of the article, “Benjamin Latrobe’s Designs for a Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River”, Dr. Michael W. Fazio offers an extensive analysis of the efforts Latrobe made to lighten the structure and to spread its weight over as large an area as possible. According to the article (Footnote 68), “The area of a 108-ft. diameter circle is 9156 sq. ft. A reasonable pile-mat bearing capacity for the blue clay soil would be about 1500 pounds per square foot; therefore 9156 sq. ft. times 1500 lbs. per sq. ft. equals 13,734,360 pounds, the allowable load that the pile-mat should have supported… If an average weight for the brick and stone masonry is assumed to be 150 pounds per cubic foot, then the total weight of the lighthouse was 36,000 cu. ft. times 150 lbs. per cu. ft. equals 5,400,000 pounds – well below the allowable load. Ruddock, in his report, said that the tower had a masonry volume of 24,667 cu. ft. and weighed 3,154,625 pounds.” Using Dr. Fazio’s analysis, one can divide the weight of Latrobe’s Lighthouse (3,154,625 pounds) into the load bearing capacity of the soil its weight was spread across (13,734,360 pounds) and conclude that the structure came in at only 23% of the soil’s load bearing capacity. Based on this analysis alone, it should be evident that weight was not cause of the structure’s failure.

Now, if one applies the same analysis to Lewis’ lighthouse, a different result comes to light. A truncated cone with a lower diameter of 28 feet, an upper diameter of 22 feet, and a height of 75 feet, has a volume of 37,000 cubic feet. Wilson's survey drawing indicates that Lewis' tower had two 18-inch thick brick walls, one inside the other with a 1-foot space in between. My conservative approximation would suggest that the tower was 25% solid, yielding a masonry volume of 9,250 cubic feet. The masonry weight of the tower would be approximately 1,387,500 pounds. Although the base of the lighthouse was 28 feet in diameter, let's assume that it sat on a foundation platform that measured 30 feet in diameter – less than 1/3rd. the diameter of Latrobe’s structure. This would yield a base surface area of 707 square feet, resulting load bearing capacity of 1,060,500 pounds. If my calculations are even remotely correct, then Lewis' tower weighed 327,000 pounds or 31% over the load capacity of the strata it sat upon! Even though Lewis’s lighthouse weighed about 1/3rd. less than Latrobe’s lighthouse, its weight was spread over a much smaller surface area. Perhaps this is why the structure had sunken 3 to 4 feet over the course of 111 years. However, if weight was the key flaw in Latrobe’s design, then Lewis’ lighthouse should have met a similar fate in as short a time. Instead, his tower, which exceeded the load bearing capacity of the soil it sat upon by 31%, continued to stand for 179 years. Winslow Lewis, through the success of his 1823 lighthouse, proved that it was not the weight of Latrobe's lighthouse which caused its untimely failure!

Friday, March 6, 2009

Aftermath of the Collapse

In a letter to the Secretary of the Treasury dated June 6, 1820, the Attorney General, William Wirt, expressed his opinion which diminished the responsibility that Winslow Lewis, et al, may have had in the failure of the first lighthouse erected on Frank’s Island. Here is the opinion in its entirety:

The contractor to build a light-house at the mouth of the Mississippi is not answerable for the failure of the foundation unless the choice of the same were left to himself.

If, on the contrary, the foundation was not that for which the United States stipulated, then the undertaker is answerable on this bond, and would be forced not merely to refund the advance which he received, but to answer in damages for the breach of his undertaking.

To the Secretary of the Treasury.

In this opinion, the Honorable William Wirt clearly leans towards the United States (and in de facto, Benjamin Henry Latrobe) as being to blame for the foundation’s failure since the specifications for the foundation were clearly defined within the contract. However, Mr. Wirt allows for a caveat that could totally overturn his opinion. If it were proven that Winslow Lewis and his sub-contractors did not follow the specifications as defined, then Winslow Lewis would be held responsible for the structure’s failure. It would appear that such evidence was never produced… Or was it???

According to the article, “Benjamin Latrobe’s Designs for a Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River” by Michael W. Fazio, inspections of the damage and the resulting reports were corresponded over the period from April, 1820 to March, 1821. At first, these reports expressed optimism that the structure could be saved. It was clear from these reports that the “portico and keeper’s house were in ruins”. However, despite its listing, one inspector expressed hope that the tower could be saved “with proper direction from Latrobe.” But this direction never came as Benjamin Latrobe died of yellow fever on September 3, 1820. By March of 1821, another inspector, Major Jenkins “concluded that new construction would be more economical than repairs.” Without having access to these reports at this time, it is impossible for me to know whether any of these inspectors actually examined the foundation. But Dr. Fazio did locate one letter from Chew to Pleasanton, dated May 26, 1821, confirming that an inspection of the foundation had been conducted independently by an engineer named “Mr. Ruddock” from “Carolina”. Here is an excerpt of Mr. Ruddock’s report as printed in Dr Fazio’s article:

"[O]n breaking up the brick floor of the portico, I found a layer of mud, two feet thick all under the area of the same, and within the wall of the foundation, and it was evidently thrown in, by the workmen, for the purpose of saving about 59,000 bricks which by the contract should occupy the place which the mud does – under this mud, I found a layer of one foot thick, of stones and sand and some oyster shells – I thus came to the planking on the top of the timbers; and found nothing but soft mud and water, among the heads of the piles; although the contract said, the heads of the piles, among the timbers should be filled with shells or solid materials, - yet none were to be found here; I then thrust a pole two inches in diameter, down among the pilings, ten feet deep with the greatest of ease; and drew the same out again – this was done in the presence of several gentlemen who stood by and saw the whole; the water immediately rose to within two inches, of the top of the ground, being 4 feet above high water. Therefore to ascertain whether this water came from below the foundation, or whether it was lodged there by rains; I excavated a hole two feet square and 6 feet deep, in the virgin strata, at about 8 inches on the outside from where the pilings were driven – and at that depth I found no water; what I dug out, was a solid blue clay strata, that weighed 95 lbs. to the cubic foot….It therefore appears that this water was one cause of the tower sinking – another cause, of the sinking of the building, was, the workman having removed the scaffold poles too soon, before the work had gotten properly dry, and consolidated all together – The falling of the walls of the rooms, and of the parapet, and of the 20 stone pillars; was in consequence of bad work, and bad mortar – the arches were not sprung, in a proper manner; as the walls were carried up too high, before they laid off the arches – the consequence of this was, the walls at the heighth; were not sufficiently solid, and weighty to stand as butments; of the semi-arches, and when the weight of the parapet pressed upon the arches after the poles were removed, the walls split, and gave way, and consequently the whole work fell to the ground."

If we accept Mr. Ruddock’s report at face value, it is clear that Latrobe’s design for the foundation was not followed; the keeper’s house and its walls were improperly constructed; and the support scaffolding was removed too quickly. However, it is unclear from Dr. Fazio’s article just who Mr. Ruddock was and why he was qualified to draw such conclusions. A bit of research on my part found within the 1822 edition of Blunt’s American Coast Pilot establishes that Mr. Ruddock was the engineer on board the Aurora Borealis, the lightship stationed at the Northeast Pass while the second lighthouse at Frank’s Island was being constructed. (I have since submitted my findings regarding Mr. Ruddock to the USCG historian since this information also establishes that the Northeast Pass lightship was the first such vessel to be stationed outside of protected waters.) With all this in mind, it would seem that Mr. Ruddock’s report would have historically established Winslow Lewis as the individual responsible for the collapse of the first Frank’s Island Lighthouse. Unfortunately for Latrobe’s legacy, Beverly Chew, the New Orleans Collector of Customs, wrote a letter to Stephen Pleasanton accompanying Mr. Ruddock’s report stating, “that the sinking of the building cannot be attributed to the causes assigned in his report.” It seems as though the now apparent actual history of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse was skewed by Mr. Chew’s not-so-professional (in my estimation) opinion as to the cause of the structure’s failure.

As taken from Dr Fazio’s article: Ruddock concluded by saying, “Had I not have seen the necessity of interfering in this business; never should I have run myself into the trouble, expense, and hazards, that I, on this account have done, But from seeing my country fleeced of its resources; without an equivalent; by men who appear to be destitute of every moral and virtuous tie, that binds human society in union, I have felt my duty; and therefore, shall not shrink from the Task.”

It is an historical injustice that Mr. Ruddock’s report was apparently skimmed over – if not wholly disregarded. Mr. Ruddock was passionate about his findings and committed to his duty in reporting them…

LIGHT-HOUSE AT THE MOUTH OF THE MISSISSIPPI.

The contractor to build a light-house at the mouth of the Mississippi is not answerable for the failure of the foundation unless the choice of the same were left to himself.

OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL,

June 6, 1820.

Sir: If the undertaker to build a light-house at the mouth of the Mississippi had contracted to build a house of particular dimensions, the choice of the foundation being left to himself, he would have been bound to have made a sufficient foundation to support the building, and would have been answerable in damages if it had failed. But, inasmuch as in the contract with Winslow Lewis the United States specify the particular foundation which they will have, I am of the opinion that, if the contractor complied faithfully with this specification in laying the foundation, he is not answerable for its failure. In this case, if either party is to be considered the insurer of the foundation, it is the party who made the selection – to wit, the United States; and the undertaker would, I think, in a suit against him, be permitted to retain so much of the advance as would cover the cost of the materials and labor furnished by him towards the work, so far as it went.If, on the contrary, the foundation was not that for which the United States stipulated, then the undertaker is answerable on this bond, and would be forced not merely to refund the advance which he received, but to answer in damages for the breach of his undertaking.

I have the honor, &c., &c., &c.,

WM. WIRT.

To the Secretary of the Treasury.

In this opinion, the Honorable William Wirt clearly leans towards the United States (and in de facto, Benjamin Henry Latrobe) as being to blame for the foundation’s failure since the specifications for the foundation were clearly defined within the contract. However, Mr. Wirt allows for a caveat that could totally overturn his opinion. If it were proven that Winslow Lewis and his sub-contractors did not follow the specifications as defined, then Winslow Lewis would be held responsible for the structure’s failure. It would appear that such evidence was never produced… Or was it???

According to the article, “Benjamin Latrobe’s Designs for a Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River” by Michael W. Fazio, inspections of the damage and the resulting reports were corresponded over the period from April, 1820 to March, 1821. At first, these reports expressed optimism that the structure could be saved. It was clear from these reports that the “portico and keeper’s house were in ruins”. However, despite its listing, one inspector expressed hope that the tower could be saved “with proper direction from Latrobe.” But this direction never came as Benjamin Latrobe died of yellow fever on September 3, 1820. By March of 1821, another inspector, Major Jenkins “concluded that new construction would be more economical than repairs.” Without having access to these reports at this time, it is impossible for me to know whether any of these inspectors actually examined the foundation. But Dr. Fazio did locate one letter from Chew to Pleasanton, dated May 26, 1821, confirming that an inspection of the foundation had been conducted independently by an engineer named “Mr. Ruddock” from “Carolina”. Here is an excerpt of Mr. Ruddock’s report as printed in Dr Fazio’s article:

"[O]n breaking up the brick floor of the portico, I found a layer of mud, two feet thick all under the area of the same, and within the wall of the foundation, and it was evidently thrown in, by the workmen, for the purpose of saving about 59,000 bricks which by the contract should occupy the place which the mud does – under this mud, I found a layer of one foot thick, of stones and sand and some oyster shells – I thus came to the planking on the top of the timbers; and found nothing but soft mud and water, among the heads of the piles; although the contract said, the heads of the piles, among the timbers should be filled with shells or solid materials, - yet none were to be found here; I then thrust a pole two inches in diameter, down among the pilings, ten feet deep with the greatest of ease; and drew the same out again – this was done in the presence of several gentlemen who stood by and saw the whole; the water immediately rose to within two inches, of the top of the ground, being 4 feet above high water. Therefore to ascertain whether this water came from below the foundation, or whether it was lodged there by rains; I excavated a hole two feet square and 6 feet deep, in the virgin strata, at about 8 inches on the outside from where the pilings were driven – and at that depth I found no water; what I dug out, was a solid blue clay strata, that weighed 95 lbs. to the cubic foot….It therefore appears that this water was one cause of the tower sinking – another cause, of the sinking of the building, was, the workman having removed the scaffold poles too soon, before the work had gotten properly dry, and consolidated all together – The falling of the walls of the rooms, and of the parapet, and of the 20 stone pillars; was in consequence of bad work, and bad mortar – the arches were not sprung, in a proper manner; as the walls were carried up too high, before they laid off the arches – the consequence of this was, the walls at the heighth; were not sufficiently solid, and weighty to stand as butments; of the semi-arches, and when the weight of the parapet pressed upon the arches after the poles were removed, the walls split, and gave way, and consequently the whole work fell to the ground."

If we accept Mr. Ruddock’s report at face value, it is clear that Latrobe’s design for the foundation was not followed; the keeper’s house and its walls were improperly constructed; and the support scaffolding was removed too quickly. However, it is unclear from Dr. Fazio’s article just who Mr. Ruddock was and why he was qualified to draw such conclusions. A bit of research on my part found within the 1822 edition of Blunt’s American Coast Pilot establishes that Mr. Ruddock was the engineer on board the Aurora Borealis, the lightship stationed at the Northeast Pass while the second lighthouse at Frank’s Island was being constructed. (I have since submitted my findings regarding Mr. Ruddock to the USCG historian since this information also establishes that the Northeast Pass lightship was the first such vessel to be stationed outside of protected waters.) With all this in mind, it would seem that Mr. Ruddock’s report would have historically established Winslow Lewis as the individual responsible for the collapse of the first Frank’s Island Lighthouse. Unfortunately for Latrobe’s legacy, Beverly Chew, the New Orleans Collector of Customs, wrote a letter to Stephen Pleasanton accompanying Mr. Ruddock’s report stating, “that the sinking of the building cannot be attributed to the causes assigned in his report.” It seems as though the now apparent actual history of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse was skewed by Mr. Chew’s not-so-professional (in my estimation) opinion as to the cause of the structure’s failure.

As taken from Dr Fazio’s article: Ruddock concluded by saying, “Had I not have seen the necessity of interfering in this business; never should I have run myself into the trouble, expense, and hazards, that I, on this account have done, But from seeing my country fleeced of its resources; without an equivalent; by men who appear to be destitute of every moral and virtuous tie, that binds human society in union, I have felt my duty; and therefore, shall not shrink from the Task.”

It is an historical injustice that Mr. Ruddock’s report was apparently skimmed over – if not wholly disregarded. Mr. Ruddock was passionate about his findings and committed to his duty in reporting them…

Friday, August 29, 2008

Construction of Latrobe's Lighthouse - 1818-1820

I must first take a moment to apologize for not updating this blog for some time. The chronology of topics has finally led me to a discussion of which I have little source material to reference. I had hoped to discover more information about the construction of Latrobe's Lighthouse before I posted this article, but I have had little success in doing so. Since I was not able to discover any new information about the construction of the first lighthouse on Frank's Island, I have decided to approach this topic by establishing an accurate time line of the events that occurred between the purchasing of materials in 1818 and the halting of construction in 1820.

According to Samuel Wilson, Jr.'s report for the Historic American Buildings Survey, jurisdiction of Frank's Island was ceded to the United States on March 2, 1818. It was then reported in the March 11, 1818 edition of the "Louisiana Courier" that the contract for building the lighthouse had been signed. By April 13, 1818 materials had started arriving by way of the Brig Triton from Boston.

The next dated reference I can find is from Dr. Fazio’s report. By July of 1818, Winslow Lewis had sent his agent, Benjamin Beal, to Frank’s Island. Joining him was Captain Edward Gardner, a customs inspector, who drove a test pile and determined there was “no doubt that a permanent building may be erected with perfect safety.” Dr. Fazio’s report then states that Beal went back to Boston to confer with Lewis. During the meeting, Beal conveyed his doubts that the island’s soil could support such a masonry structure. Despite Beal’s misgivings, construction on the lighthouse had begun by January of 1819.

In a report written by Benjamin Latrobe dated May 7, 1819, Latrobe describes a personal visit he made to Frank’s Island. In his report, Latrobe conveys his disappointment with the lack of shells and other hard materials that were to be placed among the piles. During this inspection, Latrobe did approve of the building materials (bricks and stone) that had been procured for the lighthouse’s construction. He also found some of the work to be “faithfully executed”, but Dr. Fazio’s report is unclear as to specifically which work Latrobe was referencing. Included in Latrobe’s report is a drawing of the construction site showing the foundation and temporary buildings.

In July of 1819, according to Dr. Fazio’s report, a hurricane struck Frank’s Island and “ravaged the site”. Despite this setback, by September of 1819, the base, including the keepers quarters, had apparently been completed and work on the tower had begun. A letter from Chew to Smith, dated September 20, 1819 states that “the tower of the lighthouse has settled perpendicularly”. This statement was taken from a report by Mr. Edward Hearsey, the resident superintendent of the lighthouse on Frank’s Island. Mr. Hearsey went on to describe the settling of the tower and contrasted its settlement with that of the outer base section and concluded “That there does not appear to have been any settlement in the wall of the columns, -- but rather, if anything a rise.”

Through the research I have located so far, things become unclear at this juncture. According to Dr. Fazio’s report, Latrobe read Mr. Hearsey’s report and met with him to discuss the building’s settling. Based on the information presented to him by Mr. Hearsey and “other evidence”, Latrobe concluded that the settling had stopped and construction continued. On March 14, 1820, The Speaker of the House laid before Congress a report from the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury, Stephen Pleasanton, regarding the progress being made on the lighthouse. Dr. Fazio’s report implies that this report contained the “bad news” of the structure’s failure. This is confirmed in Mr. Wilson’s HABS report which states, “that the building was settling dangerously, large cracks being produced in the walls”.

At this point, it appears all construction work on the lighthouse was ceased. According to Dr. Fazio's report, "By early April, the contractor of record, now a man named Duncan Thaxter, had abandoned the island". Several people, including architects and engineers, were called in over the course of the next year to inspect the damage. Eventually, the inspectors deemed the failure of the structure to be too costly to repair. Even before a consensus on the damage was reached, in May of 1820, the Secretary of the Treasury had requested that a “light vessel” be stationed at the mouth of the Mississippi according to “The Public Statues at Large of the United States of America” (Sixteenth Congress, Session 1, page 599).

According to Samuel Wilson, Jr.'s report for the Historic American Buildings Survey, jurisdiction of Frank's Island was ceded to the United States on March 2, 1818. It was then reported in the March 11, 1818 edition of the "Louisiana Courier" that the contract for building the lighthouse had been signed. By April 13, 1818 materials had started arriving by way of the Brig Triton from Boston.

The next dated reference I can find is from Dr. Fazio’s report. By July of 1818, Winslow Lewis had sent his agent, Benjamin Beal, to Frank’s Island. Joining him was Captain Edward Gardner, a customs inspector, who drove a test pile and determined there was “no doubt that a permanent building may be erected with perfect safety.” Dr. Fazio’s report then states that Beal went back to Boston to confer with Lewis. During the meeting, Beal conveyed his doubts that the island’s soil could support such a masonry structure. Despite Beal’s misgivings, construction on the lighthouse had begun by January of 1819.

In a report written by Benjamin Latrobe dated May 7, 1819, Latrobe describes a personal visit he made to Frank’s Island. In his report, Latrobe conveys his disappointment with the lack of shells and other hard materials that were to be placed among the piles. During this inspection, Latrobe did approve of the building materials (bricks and stone) that had been procured for the lighthouse’s construction. He also found some of the work to be “faithfully executed”, but Dr. Fazio’s report is unclear as to specifically which work Latrobe was referencing. Included in Latrobe’s report is a drawing of the construction site showing the foundation and temporary buildings.

Frank's Island - April 1819

Frank's Island - April 1819

(Lighthouse Construction Drawing by Benjamin Latrobe)

Through the research I have located so far, things become unclear at this juncture. According to Dr. Fazio’s report, Latrobe read Mr. Hearsey’s report and met with him to discuss the building’s settling. Based on the information presented to him by Mr. Hearsey and “other evidence”, Latrobe concluded that the settling had stopped and construction continued. On March 14, 1820, The Speaker of the House laid before Congress a report from the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury, Stephen Pleasanton, regarding the progress being made on the lighthouse. Dr. Fazio’s report implies that this report contained the “bad news” of the structure’s failure. This is confirmed in Mr. Wilson’s HABS report which states, “that the building was settling dangerously, large cracks being produced in the walls”.

At this point, it appears all construction work on the lighthouse was ceased. According to Dr. Fazio's report, "By early April, the contractor of record, now a man named Duncan Thaxter, had abandoned the island". Several people, including architects and engineers, were called in over the course of the next year to inspect the damage. Eventually, the inspectors deemed the failure of the structure to be too costly to repair. Even before a consensus on the damage was reached, in May of 1820, the Secretary of the Treasury had requested that a “light vessel” be stationed at the mouth of the Mississippi according to “The Public Statues at Large of the United States of America” (Sixteenth Congress, Session 1, page 599).

Thursday, January 10, 2008

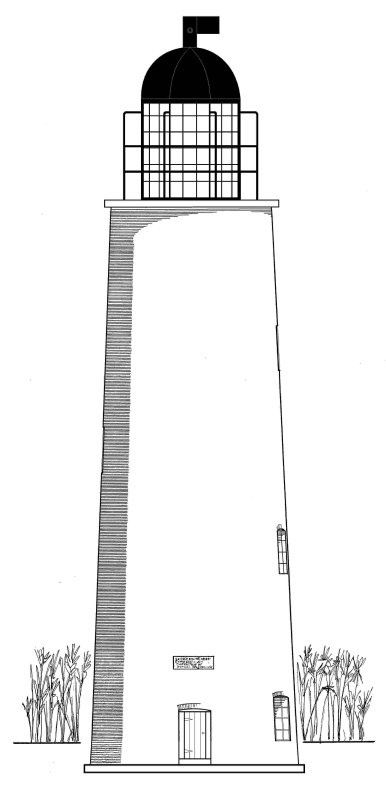

A View of the Second Lighthouse

You may have noticed a drawing of the 1823 Frank’s Island Lighthouse towards the top of the main page. One of the things that first drew me to the Frank’s Island Lighthouse was the aerial photograph of the tower ruins taken in 1995 by Bob and Sandra Shanklin. What intrigued me about the photograph was the fact that the lantern was missing. As I began researching the structure, I discovered that no known drawings or photographs existed which depicted a complete lantern. For the longest time, I questioned whether the original lantern had been reused or whether Lewis’ tower was capped with one of his signature “birdcage” lanterns. The photographs from Samuel Wilson’s 1935 report for the Historic American Buildings Survey show the remains of a railing system consistent with a “birdcage” lantern. A report from the 1855 U. S. Congressional Serial Set states that the “dome” was painted. Since the lantern from the first lighthouse was equipped with a stone cap, my conclusion based on these findings is that the 1823 lighthouse erected on Frank’s Island featured a “birdcage” lantern.

Once I came to this conclusion, I began searching for a scale drawing of a Lewis “birdcage” lantern. This was more difficult than I originally thought considering it has been noted that Lewis had a canned set of tower designs. I eventually discovered such a plan in David Cipra’s first book, “Lighthouses & Lightships of the Northern Gulf of Mexico” published for the Department of Transportation in 1976. This book is now out-of-print; but if you can locate a copy at a reasonable price, I would recommend purchasing it. There are pictures and information contained in this 62-page publication that were not included in his second book.

With scale drawings of both the Lewis’ tower and lantern in hand, I was able to overlay the two images in scale to generate a single image. I then projected the submerged base of the tower from Wilson’s drawing and added the remaining few feet at the bottom. The "Frank’s Island Lighthouse – 1823" drawing towards the top of the blog’s main page is the result. I hope this drawing serves to give future generations a fairly accurate representation of the lighthouse that stood at the Northeast Pass of the Mississippi River for 179 years.

Once I came to this conclusion, I began searching for a scale drawing of a Lewis “birdcage” lantern. This was more difficult than I originally thought considering it has been noted that Lewis had a canned set of tower designs. I eventually discovered such a plan in David Cipra’s first book, “Lighthouses & Lightships of the Northern Gulf of Mexico” published for the Department of Transportation in 1976. This book is now out-of-print; but if you can locate a copy at a reasonable price, I would recommend purchasing it. There are pictures and information contained in this 62-page publication that were not included in his second book.

With scale drawings of both the Lewis’ tower and lantern in hand, I was able to overlay the two images in scale to generate a single image. I then projected the submerged base of the tower from Wilson’s drawing and added the remaining few feet at the bottom. The "Frank’s Island Lighthouse – 1823" drawing towards the top of the blog’s main page is the result. I hope this drawing serves to give future generations a fairly accurate representation of the lighthouse that stood at the Northeast Pass of the Mississippi River for 179 years.

Thursday, December 27, 2007

Reading the Morning Paper

I sat down to read the morning paper and noticed an article about the Mississippi Light-house. Of course, it was not today's paper, but a Bostonian newspaper from August 1, 1817 called "The Yankee". Although the article only briefly mentions the lighthouse to be erected on Frank's Island, it does provide a window into the past. The significance of the article is how it illustrates the pride and desire of the people of this young country to be self-reliant. Below is the article in its entirety...

MISSISSIPPI LIGHT-HOUSE.

In the proposals sometime since published in this paper, for erecting a light-house at the mouth of the Mississippi, the attention of persons disposed to contract for effecting this object was directed to the circumstance of the existence of quarries of free stone at the Havana. We are now favored, from the revenue office, with the following communication, made by a respectable inhabitant of the Philadelphia. Its importance, not merely in respect to this object, but generally to the country on the sea board, is manifest.

Geological Memorandum – Building Stone in Florida.

The geological base of the whole peninsula of Florida, and contiguous islands, is, what is commonly called, free stone, though it is rather an indurated marble, such as is found at Portland and Bath, England, and in the quarry in which the capitol of Washington is built, from the quarries on the Potomac.

At from eight to ten feet below the surface, this stone is found in the peninsula of Florida; the surface, or upper stratum is a vegetable mould, occasionally mixed with a delicate granite sand, and this is rarely more than two feet deep; at the depth there is a stratum of fine granite sand, white and red intermixed with a ferruginious earth, but in a small quantity; this sand rarely exceeds three feet thick, and much resembles the same kind of sand found about six to eight feet under Philadelphia. Below this second stratum of sand, is a fine stratum of whitish clay or marble, which is usually found of from two to three feet thick, and is an admirable article to mix wherever sand protrudes above the vegetable stratum.

Immediately below the mar[b]le, is a deep stratum of whitish stone, which appears to be a composition of petrified or decomposed marine shells; this has been as far as penetrated, which has been about 18 to 20 feet deep. This stone is more elevated above the general level in the island of Anastasia, directly opposite the town of St. Augustine.

This island is about 25 miles long, and separated from the main land by an arm of the sea, which is called Mantanzas river; the quarry of which the old fortifications and the houses of St. Augustine were built, is open, and directly opposite St. Augustine. The navigation round the island is good – there is only eight feet water on the bar of St. Augustine, though it was formerly as deep as three fathoms on the bar.