I had concluded in my prior post that the 1816 study favored Frank’s Island mostly due to its proximity to the Northeast Pass instead of the firmness of the soil. Even though the Frank’s Island location was ideal for navigational reasons, the report indicates that a thorough soil study was done on all of the proposed locations. It was the conclusion of the three representatives that “It is the most solid of those in the neighborhood, and even more so than that selected by Mr. DeMunn.” The report specifies that soil samples were taken at depths of up to fifty feet. Like DeMunn, Latrobe and company found the clay to be harder the deeper they dug. The importance of noting these observations is to point out the extensive efforts that were taken prior to construction to make certain that an appropriate location was selected for “The Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River.”

Another observation from the report is that the chosen site for the lighthouse on Frank’s Island had strategic advantages should the structure come under attack. Shoals and other features of the island made a direct advance rather difficult. In 1816, the memories of the War of 1812 and the 1814 Battle of New Orleans were still fresh on the minds of all involved in this project. The threat of attack was very real. A complex fortification system to defend New Orleans was also being planned during this time. Therefore, it can be concluded that a structure which could withstand bombardment and fire would be preferable to one that could not. Although the report does not state the exact reasons, (but a June 15, 1817 letter from Samuel Smith to Daniel J. Patterson, et al might) it does at least show that there was a preference by Washington for a “stone or brick building” instead of a wooden tower.

It had been my impression until reading this report that Benjamin Latrobe was so obsessed with constructing a masonry lighthouse on the soft soil of the Mississippi Delta that he overlooked the obvious fallacy of such a structure’s inevitable collapse. The report prepared by Patterson, Latrobe, and Duplessis shows that the use of brick or stone was a preference by consensus. This report also defines the care taken to make sure that Frank’s Island was the proper location for the lighthouse noted by three major factors: visibility, firmness of the ground, and resistance to attack. It is interesting to note that the 1816 plans for the lighthouse now located in the National Archives were apparently submitted along with this report to Samuel Smith, Commissioner of Revenue. Therefore, all three representatives could be credited for creating the final set of plans for the Mississippi River Lighthouse.(See Addendum Below) The planning for a lighthouse at the mouth of the Mississippi River was not an endeavor that Benjamin Latrobe took lightly, nor was it an endeavor that he pursued alone. Incidentally, the efforts to fortify New Orleans resulted in numerous masonry fortifications erected on marshy wetlands – many of which are still standing!

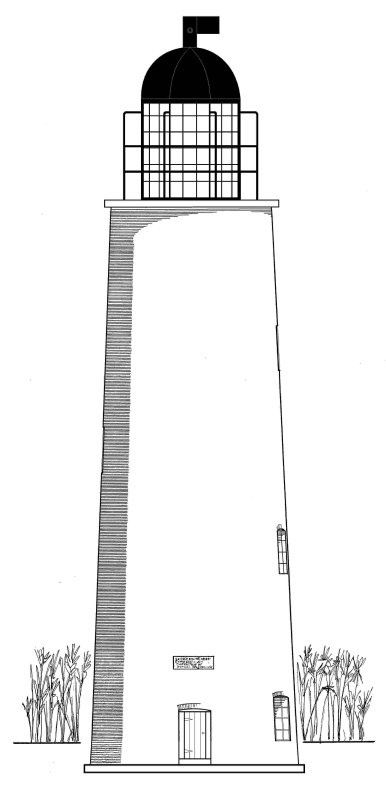

Addendum (9/16/2009) - It appears as though the plans included with the aforementioned report were not the final set of plans. Instead, what could be considered a preliminary set of plans were submitted. Dr. Fazio speculates these plans represent an earlier design concept that Benjamin Henry Latrobe had envisioned for the Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River. After referring back to Dr. Fazio's article, I noted that the final set of plans were sent by Henry Latrobe to his father and were received in June of 1817. Whether or not Patterson and Duplessis had any involment in the development of the final set of plans is uncertain at this point. Below is a copy of Henry Latrobe's 1816 drawing from Cipra's "Lighthouses and Lightships of the Northern Gulf of Mexico".