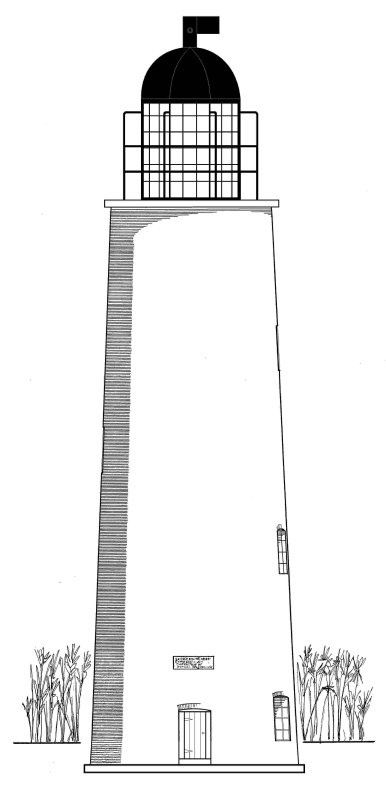

MISSISSIPPI LIGHT-HOUSE.

In the proposals sometime since published in this paper, for erecting a light-house at the mouth of the Mississippi, the attention of persons disposed to contract for effecting this object was directed to the circumstance of the existence of quarries of free stone at the Havana. We are now favored, from the revenue office, with the following communication, made by a respectable inhabitant of the Philadelphia. Its importance, not merely in respect to this object, but generally to the country on the sea board, is manifest.

Geological Memorandum – Building Stone in Florida.

The geological base of the whole peninsula of Florida, and contiguous islands, is, what is commonly called, free stone, though it is rather an indurated marble, such as is found at Portland and Bath, England, and in the quarry in which the capitol of Washington is built, from the quarries on the Potomac.

At from eight to ten feet below the surface, this stone is found in the peninsula of Florida; the surface, or upper stratum is a vegetable mould, occasionally mixed with a delicate granite sand, and this is rarely more than two feet deep; at the depth there is a stratum of fine granite sand, white and red intermixed with a ferruginious earth, but in a small quantity; this sand rarely exceeds three feet thick, and much resembles the same kind of sand found about six to eight feet under Philadelphia. Below this second stratum of sand, is a fine stratum of whitish clay or marble, which is usually found of from two to three feet thick, and is an admirable article to mix wherever sand protrudes above the vegetable stratum.

Immediately below the mar[b]le, is a deep stratum of whitish stone, which appears to be a composition of petrified or decomposed marine shells; this has been as far as penetrated, which has been about 18 to 20 feet deep. This stone is more elevated above the general level in the island of Anastasia, directly opposite the town of St. Augustine.

This island is about 25 miles long, and separated from the main land by an arm of the sea, which is called Mantanzas river; the quarry of which the old fortifications and the houses of St. Augustine were built, is open, and directly opposite St. Augustine. The navigation round the island is good – there is only eight feet water on the bar of St. Augustine, though it was formerly as deep as three fathoms on the bar.

This free stone may be cut out of the quarry with a carpenter’s hand-saw, as soon as the upper layer is removed, as it is very soft like cheese, in the quarry; but when some time exposed to the air, becomes so hard as to turn the edge of a tempered chissel. It can be carried from the quarry to the vessels with very little difficulty, being close upon the shore. It would be well worth while to procure that stone for all our light-houses. The quality is the same as that of Havana, only reputed to be whiter, and to contain very little iron veins.

At from eight to ten feet below the surface, this stone is found in the peninsula of Florida; the surface, or upper stratum is a vegetable mould, occasionally mixed with a delicate granite sand, and this is rarely more than two feet deep; at the depth there is a stratum of fine granite sand, white and red intermixed with a ferruginious earth, but in a small quantity; this sand rarely exceeds three feet thick, and much resembles the same kind of sand found about six to eight feet under Philadelphia. Below this second stratum of sand, is a fine stratum of whitish clay or marble, which is usually found of from two to three feet thick, and is an admirable article to mix wherever sand protrudes above the vegetable stratum.

Immediately below the mar[b]le, is a deep stratum of whitish stone, which appears to be a composition of petrified or decomposed marine shells; this has been as far as penetrated, which has been about 18 to 20 feet deep. This stone is more elevated above the general level in the island of Anastasia, directly opposite the town of St. Augustine.

This island is about 25 miles long, and separated from the main land by an arm of the sea, which is called Mantanzas river; the quarry of which the old fortifications and the houses of St. Augustine were built, is open, and directly opposite St. Augustine. The navigation round the island is good – there is only eight feet water on the bar of St. Augustine, though it was formerly as deep as three fathoms on the bar.

This free stone may be cut out of the quarry with a carpenter’s hand-saw, as soon as the upper layer is removed, as it is very soft like cheese, in the quarry; but when some time exposed to the air, becomes so hard as to turn the edge of a tempered chissel. It can be carried from the quarry to the vessels with very little difficulty, being close upon the shore. It would be well worth while to procure that stone for all our light-houses. The quality is the same as that of Havana, only reputed to be whiter, and to contain very little iron veins.