Gallatin then turned to Benjamin Henry Latrobe for assistance in this matter. It is believed that Latrobe studied under John Smeaton, builder of the famous Eddystone Lighthouse. My impression is that Latrobe looked upon Smeaton as a mentor. If it is true that Latrobe studied under Smeaton, therein lies an interesting contrast. Whereas the challenge of the Eddystone Lighthouse was to adhere a masonry structure to a small rock inundated by harsh seas, Latrobe faced an equally difficult but somewhat different challenge – to secure and “float” a masonry structure on an ancient deposit of soft blue clay. Dr. Fazio’s article covers Latrobe’s design process and evolution in detail. For the sake of this discussion, we should concentrate on Latrobe’s final lighthouse design and focus on the foundation, sub-structure, and steps that Latrobe took to reduce the weight of his tower.

In addition to the lighthouse design, the soil conditions of Frank’s Island are of equal consideration. Frank’s Island was deemed to be a suitable location for a masonry lighthouse on two different occasions. According to Dr. Fazio’ article, in 1806 a man named Louis De Mun took soil samples from several possible locations for the proposed lighthouse. Although Frank’s Island was not his first preference, he concluded:

“I like the ground of the island well. It will bear anything that can be put upon it. The alluvium of which it consists, - Blue clay - is the alluvium also of our Atlantic Rivers, and like the clay on the Mississippi, the deeper you dig the harder it becomes. - The foundation of a stone building may be laid deep, and yet put up on piles, - for the clay is perfectly watertight.”

At this point, I as a blogger have to admit my own limitations… I am not a civil engineer, nor am I a geologist familiar with the alluvium that forms the Mississippi Delta. Therefore, I cannot begin to suggest how accurate De Mun’s conclusions are by today’s science. It would be great if a qualified individual could step in and offer an educated opinion.

In 1813, as reported in Dr. Fazio’s article, Frank’s Island was once again selected as the location for the Mississippi River Lighthouse by a group of three representatives, including Latrobe’s son, Henry. This decision appears to have been based mostly upon the accessibility and navigability of the Northeast Pass and not upon the soil conditions of the island. The final documented inspection of Frank’s Island was done by an engineer after the failure of the original structure. His analysis indicated that the “solid blue clay strata” “weighed 95 lbs. to the cubic foot” according to the Fazio article.

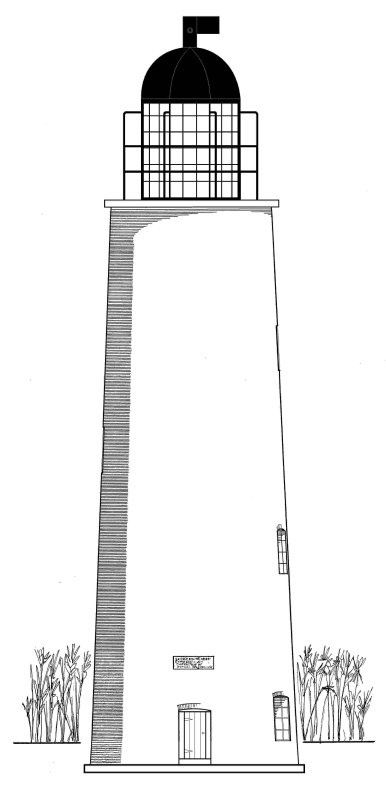

With a general consensus that the soil of Frank’s Island would support a masonry structure, Latrobe worked on a design that would allow for the weight of the tower to be spread across a much-wider base. His tower and base designs used a series of “inverted arches” to hollow out, and thus lighten the structure as much as possible. Latrobe also specified a unique and integral design for the structure’s foundation using a cypress piling and planking system. One of Latrobe’s greatest concerns was that the U.S. Congress, through its policy of awarding bids to the lowest bidder, would end up hiring a contractor not qualified to execute the lighthouse’s construction in accordance with his design. Therefore, Latrobe drafted the bid with excruciating detail – possibly warding off any prospective bidders. This opened the door for Winslow Lewis to enter the picture. What is most important to note is that Latrobe specifically designed his lighthouse with the soil conditions of Frank’s Island foremost in his mind. One notices, with a simple glance at the drawing of his lighthouse, its uniquely wide base. Despite the failure of the original structure, if there is any evidence to indicate that its builders did not follow Latrobe’s design to the letter, one should at least contemplate the possibility that the Mississippi River Lighthouse would have been a success had it been constructed properly.

4 comments:

Hi,

I too have taken a big interest in the Frank's Island Lighthouse, I used to have a webpage about it which included a short history and some pictures...I also had a drawing of my own doing that showed my idea of what the 2nd Tower looked like. Have you read "Lighthouses and Lightships of the Northern Gulf of Mexico" also by Cipra? It contains some good info about the FI lighthouse but it's now out of print. If you e-mail me, Zachary3@gmail.com, I'd be happy to scan the page for you

What happened to the government inspection of the foundation of Latrobe's Tower?

If I recall, other reports claim the condition of payment was based on inspections that Lewis built the entire Lighthouse and foundation according to design specifications. Perhaps, the web page (http://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=814) thought full inspections were completed because the federal government paid Winslow Lewis?

Debbie,

There may be a question as to whether or not the stipulation for a government inspector to be present throughout the construction was truly written into the contract. According to Dr. Fazio’s article, “an on-site supervisor with appropriate qualifications and whom Lewis later claimed he had required for undertaking the project had not been found.” It seems a trip to the National Archives for a look at the original contract would be the only way to tell if the stipulation for an on-site inspector had been written in. The only documented inspection of the foundation was performed by Latrobe himself. In his report he expressed “disappointment” with the lack “of hard materials” to fill the “reversed arches”. This inspection was apparently superficial and its primary purpose appeared to be for Latrobe to approve the construction materials that Beal had procured.

As to whether or not Latrobe’s design was followed to the letter, Dr. Fazio states “Beal almost immediately began requesting changes in both the materials and the construction methods specified by the Latrobes.” Now I am not certain if these “requests” were approved or if they were executed without formal approval. A drawing of the construction site by Latrobe from his inspection done in April of 1819 shows the foundation and the beginning stage of the “inverted cupola” for the tower. None of the other reversed arches are shown in the drawing. If it is true that a qualified inspector was not present for most of the initial construction, then it remains a question in my mind as to whether or not Latrobe’s design was followed. Again, with limited documentation available, it seems access to the source documentation at the National Archives may provide some clarification to this speculation. Furthermore, as I move forward into discussing the actual collapse and post-inspection, I believe that the popular story behind the failure of Latrobe’s lighthouse may be called into question.

Thank you for your post.

Jay

Hi, Jay

Seems like the popular inspection story quoted below is highly suspect.

"Lewis insisted on having an inspector on site to verify his strict adherence to the proposed design. Lewis believed this safety measure would exonerate him in case the project failed." Wonder what sources were used by the web author?

Looking forward to reading more about this Lighthouse mystery!

Post a Comment