Most journeys begin with a destination in mind. On this journey, the destination was unclear. In this case, there were two lighthouses – one that was short-lived and one that had recently collapsed. Their location was, at one time, known as Frank’s Island, Louisiana – located at the Northeast Pass of the Mississippi River. Today, nothing remains of Frank’s Island. The island has been consumed by erosion and is now totally engulfed by a body of water called Blind Bay.

Many people are aware of the history behind the Frank’s Island Lighthouses. President Thomas Jefferson ordered Congress to establish a navigational beacon to mark the entrance to the Mississippi River. The lighthouse that Jefferson had in mind was no ordinary lighthouse. He wanted a monument to show the world that the Louisiana Territory no longer belonged to the French. To design such a grand lighthouse, Congress selected renowned architect and engineer, Benjamin Henry Latrobe – the designer of the United States Capitol. Eventually, Frank’s Island was chosen as the location; but a little spat between the United States and England, called the War of 1812, got into the way. Finally, in 1818 Congress authorized construction of the lighthouse and work began. The not-yet-famous lighthouse builder, Winslow Lewis, was awarded the contract to construct the lighthouse. There are questions as to why the “Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River” began to settle severely and develop cracks; but the original lighthouse had to be torn down and a new one was erected in its place. The second lighthouse, designed and built by none other than Winslow Lewis, was completed in 1823.

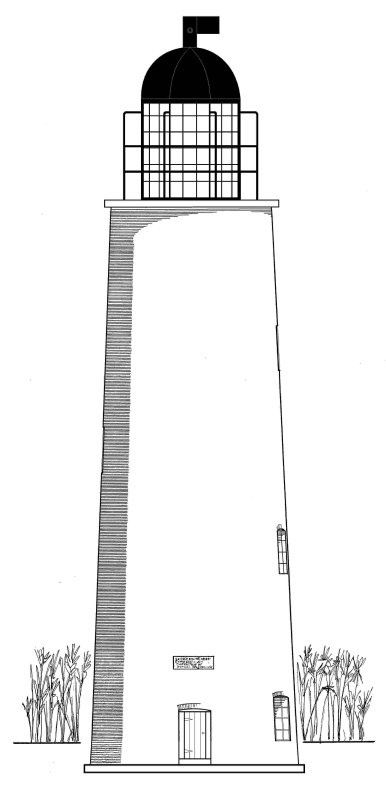

At this point, the history of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse becomes vague. There are no known pictures of the structure with a complete lantern room. As other entrances to the Mississippi River became more popular, the Northeast Pass and the Frank’s Island Lighthouse were abandoned in 1856. The journey does not continue again until 1934 when architect and descendant of Latrobe, Samuel Wilson, Jr., inspected the ruins of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse for the Historic American Buildings Survey. As a result of this survey, he composed a written report, took several black and white photographs, and drew a scale drawing of the tower. One of the most intriguing elements of Wilson’s inspection is a photograph of a marble builders marker set into the brickwork of the lighthouse, just above the doorway. The marker reads, “Erected in 1823, Contracted for by Winslow Lewis of Boston, Executed by Benjamin Beal and Duncan McB. Thaxter.” All three of these gentlemen are credited in the construction of the first lighthouse at Frank’s Island. What really makes this marker stand out is an observation that Samuel Wilson makes in his report. He noted that the date on the marker did not appear to be the original date. Apparently the “3” had been recarved over a “0” making the date 1820 – the year that Latrobe’s lighthouse had been erected. Is it possible that this builders marker from the second lighthouse served as a builders marker for the original lighthouse?

The next step of the journey begins and ends with an aerial photograph taken of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse in 1995. By 2002, the ruins of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse collapsed into Blind Bay – eventually meeting the fate of its predecessor. The lighthouse is now all but forgotten. The construction of the original lighthouse is remembered as a sort of folly; there are no outstanding photographs of either lighthouse; and the only significant remnant that could possibly be tied to both structures collapsed into Blind Bay and is probably covered by several feet of dark mud. But is that the end of the story? Is Thomas Jefferson’s vision of a grand lighthouse at the mouth of the Mighty Mississippi to end with the unheard collapse of a second lighthouse? Or will this marble marker one day be uncovered by a storm and be discovered by some future historian who will carry on its legend and its legacy?

It has been said that a photograph is worth a thousand words. In this case, a closer inspection of a photograph of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse taken in 1995 by Bob and Sandra Shanklin yielded a whole new beginning to this journey. It just so happens that the 1995 photograph was taken of the east face of the tower. The picture taken in 1934 by Samuel Wilson, Jr. is also of the east face. The difference between the two photographs is the marker from the earlier picture is missing in the more recent picture! Where could it have gone? Could it be in a museum? Was the marble slab removed by vandals and sold to a private collector? At this point in the journey, the destination became unclear.

Fortunately, the journey continued not far from where the last phase ended. Bob Shankin vaguely remembered that a marker from the Frank’s Island Lighthouse was on display at one of the old Civil War forts around New Orleans. As history would have it, New Orleans was heavily fortified at the time of the Civil War by no fewer than eight active fortifications. However, only two of these old forts are open to the public – Fort Pike in New Orleans and Fort Jackson in Buras, Louisiana.

Now there is a fork in the road. With these two forts being about 55 miles apart it should not be difficult to get into a car and visit both forts in one day. Up until August 29, 2005, this trip would have been no problem. However, both forts were overwhelmed by the forces of Hurricane Katrina. Fort Pike suffered a direct blow - opening three-foot wide cracks in its walls. Fort Jackson was flooded by Hurricane Katrina and then re-flooded almost one month later by Hurricane Rita. So, no matter which direction is taken, the journey is cut short.

It has been a year-and-a-half since Hurricane Katrina. The city of New Orleans is slowly coming back to only a fraction of what it once was. The people in New Orleans and its outer-lying parishes are a proud people doing the best they can to restore their homes and their lives. What they knew to be beautiful, what they knew to be mundane, most of everything they knew has been destroyed. What has been reclaimed of their memories has been accomplished through hard work and patience. It would seem that a long forgotten remnant of history would have no place in their current strifes. But that is not the case…

A few quick phone calls to the Louisiana Office of State Parks made it apparent that Fort Pike had not been forgotten. Work was done to clean the layer of muck and debris that was deposited throughout the fort’s interior. Any artifacts belonging to the Fort Pike Museum were gathered, cleaned, and preserved for future display. Engineers have been called in to assess the damage caused to the fort’s structure by Hurricane Katrina. It will be some time before this fort will be open to the public – if it is ever opened again. One item that was not listed in the fort’s inventory of artifacts – a marble marker removed from the Frank’s Island Lighthouse. So, the journey continues…

Plaquemines Parish was so heavily hit by Hurricane Katrina that only the first few miles of Highway 23 were accessible for weeks. As an outer-lying parish, Plaquemines Parish is having a much more difficult time getting back on its feet. The same is true for Fort Jackson. Whereas Fort Pike is managed by the Louisiana Office of State Parks and is funded by the State, Fort Jackson is managed by the local municipality. This makes funding for restoration efforts more difficult. Despite these difficulties, the people in Plaquemines Parish were very helpful and courteous. The Parish Historian, Rod Lincoln, was very knowledgeable about Frank’s Island Lighthouse and all of the other lighthouses that marked the Passes. Without hesitation, Mr. Lincoln was able to confirm that the marble marker from the Frank’s Island Lighthouse is now on display at Fort Jackson. However, like its sister fort, Fort Jackson is also closed to the public for an indefinite period of time.

At this point, the mystery is solved and the story ends. But, as in every good story about a journey, there is a hero. The hero in this story is a Mississippi River boat pilot named Captain Mark Delesdernier, Jr. As a child, Captain Delesdernier had the opportunity to frequent the Frank’s Island Lighthouse – its lantern-less tower now standing in waist-deep water. He was captivated by the marble cornerstone of the lighthouse and read its inscription often. Over time, the mortar around the marker gave way, and the marble slab became loosened from its one-hundred-fifty-year-old resting place. At some point, the bottom right corner of the marker was damaged and a small section broke off. By the late 1960’s, the cornerstone was released from its encasement and it fell into the water. On a warm sunny day, Captain Delesdernier dove into the water and began feeling around for the marker. With luck, he found its resting place at the bottom of the bay! He used a small flatboat and a rigging of pipes and rope, positioned through the doorway of the old lighthouse ruins, to raise the eight-hundred-pound slab of marble from the water. As soon as he got the marker into the boat, the weight of the marble slab caused the boat to sink – requiring Captain Delesdernier to get a bigger boat. Eventually, he donated the cornerstone to the people of Plaquemines Parish. A new resting place was hewn out of the brick interior of Fort Jackson, and the marble marker was re-encased into its new home – once again on display. A metal plaque was then placed over the Frank’s Island Marker by the Plaquemines Parish Commission Council to illustrate the marker’s history and to honor its dedication. Whether or not Captain Delesdernier truly knew the history behind the lighthouse and the marker, he is a hero for saving this piece of history before it was lost to the muddy waters of Blind Bay and forgotten.

At the end of every journey, one should reflect and take the time to look at the pictures. In this journey, there are a few things to ponder. The journey began with President Thomas Jefferson when he ordered that a monumental lighthouse was to be erected. It then went to Benjamin Henry Latrobe and a grand lighthouse was designed. Next it fell into the hands of Winslow Lewis. An exquisite lighthouse was built, only to be torn down almost immediately due to a failure of its foundation. At this point, did Winslow Lewis recover the builders marker from the first lighthouse and save it for a future replacement? One only has to look at Samuel Wilson’s photographs of the Frank’s Island Lighthouse to realize the answer. There is nothing elaborate about the second lighthouse built in 1823 with the exception of the marble marker. Lewis made only one commitment to Congress in regards to the second lighthouse – that he would guarantee its foundation. Unlike his predecessor, Benjamin Latrobe, Lewis was not hired to design a monument. He just had to build the 1823 lighthouse so that it would not collapse. To have such a large piece of marble cut and shipped from the East Coast would have been an unnecessary expense for Lewis. Therefore, it is probable that this marker is the only remaining identifiable object to have served as part of the structure for the Lighthouse at the Mouth of the Mississippi River as ordered by President Thomas Jefferson. Incidentally, Fort Jackson was erected around the same time as the lighthouses at Frank’s Island were being constructed. It is somewhat ironic that a fortification built to guard the first Capitol of the Louisiana Territory now stands to shelter a piece of a lighthouse that once guided sailing vessels safely to the mighty river that runs through it – two remnants of Thomas Jefferson’s legacy, living in the past, huddling together as though waiting out another storm.

Author's Note - At the time I had written this article, I thought I was really onto something, having discovered a historical and structural link between the two lighthouses constructed on Frank's Island. My later research findings show that authors David L. Cipra and Janice P. Buras had also written about the marble marker and its commonality to both lighthouses. In her book, "Way Down Yonder in Plaquemines Parish", Ms. Buras tells the story of the marker's recovery and its current placement in Fort Jackson. Had I discovered her book before I began my quest to find the marker, it would have surely saved me some time and effort! It is highly likely that Samuel Wilson, Jr. also made the same connection of the marker having been used in the construction of both lighthouses, but I have not been able to verify this as yet. The pictures below illustrate the marker's journey from Frank's Island to Fort Jackson...

Close-up of Lighthouse Doorway from Latrobe's Drawing Showing Marker

Close-up of Lighthouse Doorway from Latrobe's Drawing Showing Marker

.jpg) Picture of the Marble Marker - Historic American Buildings Survey

Picture of the Marble Marker - Historic American Buildings Survey

Picture of Marble Marker now at Fort Jackson - Buras, Louisiana

Picture of Marble Marker now at Fort Jackson - Buras, Louisiana

Close-up of Plaque Above Marker

Close-up of Plaque Above Marker

Last Two Pictures are Courtesy of Rod Lincoln, Plaquemines Parish Historian

2 comments:

This is a fantastic job documenting the history of these lighthouses. I am doing research on a man involved with the original lighthouse, Lewis DeMun. He was a draftsman and pupil of Latobe's. I am creating a blogspace with information about this man, and was wondering if you would mind if I could post a link to your site?

Will,

Thank you for your nice comments! I know I ran across Lewis DeMun in my research. He was the surveyor who originally selected Royal Island as the site for Latrobe's lighthouse. Feel free to link to this site. I am looking forward to reading your blog!

Jay

Post a Comment